Quo vadis, Arroyo?: Attempts to amend the Philippine Constitution in context

Posted by alternaterealitiesph on November 6, 2009

Introduction:

The latest attempt to amend the Philippine Constitution, through House Resolution 1109 of the Philippine Congress, should not be seen as an incident limited to the current political milieu of the Philippines, or to the presidency of Gloria Arroyo alone. Rather, it is the culmination of a long struggle between political forces in the Philippines to create a political order that best suits the power dynamics between ethnic groups, between national and local politicians, and between the legislative and executive officials.

Long seen as the aberrant nation of Southeast Asia, the Philippines has not been a stranger to crises. However, the evolution and development of Philippine democracy provides an instructive case of how an Asian nation has melded Western conceptions of governance and politics with its own culture, and how the resulting fusion continues to produce change. Philippine democracy, far from being static, continues to produce lessons for other nations outside the West that are only beginning to chart their way to democracy. The fact that the Philippine government has undergone several iterations alone is instructive in evaluating how certain forms of government may not be suitable to young nations, especially those with a history of despotism.

A brief history lesson

Philippine liberal nationalist thought had its roots in the rise of the ilustrado movement in the late 19th century, after the liberal revolutions of 1848 in Europe and the opening of the Suez canal allowed ideas to flow and filter through to the only Spanish colony in Asia. This movement culminated in the 1896 Philippine Revolution that briefly attained independence for the country. The revolutionary government formed at Malolos in 1899 established a unicameral national assembly, which also had the power to elect the President. The President, in turn, had his own cabinet, independent of the assembly. This was designed to ensure a strong government that could act decisively, as tensions were becoming apparent with President Emilio Aguinaldo’s erstwhile allies, the Americans under Commodore George Dewey.

The Philippine-American war and the resulting American occupation imposed American institutions and conceptions of democracy on the Philippines. This produced a semi-democratic form of government that incorporated limited suffrage for land-owning men. It also introduced the concept of a bicameral government for the first time: the 1907 Philippine Commission had a bicameral chamber. The Philippine Legislature instituted by the 1916 Jones Law retained the same structure. This setup provided a forum for aspiring Senators such as Manuel Quezon and Sergio Osmeña, who both later became Presidents of the Philippines, to build political capital and to advocate for independence from the US. Both jockeyed for power in the only national elected body in the land until the 1935 Constitution established a nationally elected Presidency. The new Philippine Commonwealth introduced a unicameral National Assembly, which was the second attempt to institute a unicameral legislature, but did not last. On the eve of World War 2, constitutional amendments restored the bicameral structure from before 1935 and allowed the President to seek reelection. The subsequent Japanese invasion spawned a client Philippine Republic with its own constitution, and featured a strong executive, who was appointed by a unicameral national assembly. This was the third attempt to establish a unicameral legislature, which was ultimately short-lived and dispatched upon the return of the Americans and the Commonwealth in 1944. The 1935 Constitution was then restored, paving the way for an independent republic in 1946. For the next 25 years, a stable equilibrium existed between the executive and legislative branches of government, where the Senate checked Presidential power, and where future Presidents built their reputation in the Senate.

However, by the late 1960’s, it was apparent that political decay had set in. While generating political stability, the Constitution also enabled politicians from the rival Nacionalista and Liberal Parties to maintain a patron-client relationship with their constituencies that protected the feudal economic structure of the country. As considerable amounts of money were required to campaign for and win in elections, only those with considerable financial resources could viably run for office. The landowning class was able to monopolize capital in a society that was still fundamentally agricultural, which meant that they had the means to win elections, fairly or not. The lack of a viable opposition within government permitted unfettered rent-seeking. As the landed class passed laws that were nakedly biased towards their interests, the authority they exercised as elected officials effectively legitimized their rent-seeking activities.

The need for reforms was apparent by the end of the decade, and when President Ferdinand Marcos convened a Constitutional Convention in June 1971, reformists saw an opportunity to design a government that could be more accountable and also address social concerns. Interestingly, the list of recommendations that the delegates submitted included a shift to a parliamentary system, with an indirectly elected Prime Minister as a foil to the abuse of Executive power. However, by then, President Marcos already had plans to extend his tenure as President, and declared martial law a little more than a year later on September 21, 1972. In the process, he jailed many of the delegates of the Convention, and forced the remaining ones to modify the Constitution to allow a strong President to rule alongside a weaker Prime Minister. This fourth attempt at establishing a unicameral legislature by amending the Constitution was distorted by Marcos’ imposition of martial law, and the credibility of the civilian government that Marcos finally permitted in 1981 was damaged by the lack of free elections and the subservience of Prime Minister Cesar Virata to Marcos himself.

In due course, Marcos was deposed after it became apparent that his misrule had destabilized the country both politically and economically. President Aquino, wishing to disassociate her new government from the Old Order of Marcos, called for a new constitution. The resulting 1987 Constitution was heavily inspired by the 1935 Constitution, but limited executive powers and prevented the President from seeking reelection. This effectively restored the pre-Marcos political order with all its attending ills. The Congress continued to be dominated by provincial oligarchs, and political reforms proceeded at snail’s pace. The problems of the 1987 system became most apparent during the 2000-2001 impeachment trial of Joseph Estrada. While the impeachment process allowed for a thorough investigation of the misdeeds of the executive, and also allowed the President to defend himself/herself, it was also tortuous and acrimonious, requiring separate majorities in both the lower and upper houses to succeed. As the President’s allies dominated the Senate, there was no possibility that the complaint could succeed. As a result, extra-Constitutional measures were used by Estrada’s opponents, who deposed him in civilian-military coup that was later endorsed by the Supreme Court. At the time, political commentators noted that a parliamentary form of government would have enabled a much simpler method of removing the current head of government, and could have restored public trust in government institutions (even if its personalities were discredited).

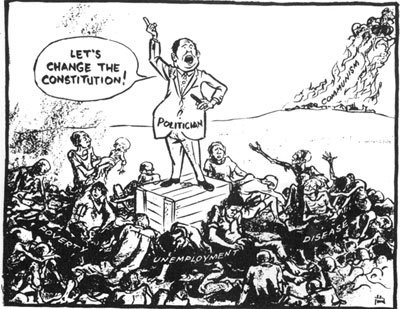

In the 22 years since the creation of the 1987 Constitution, Presidents Ramos and Arroyo have both attempted to amend it. Both have ostensibly done so institute reforms. In Ramos’ case: to alter the provisions of the Constitution limiting foreign ownership in specific industries to encourage foreign investment. Arroyo has adopted Ramos’ justification and added her own: to restore a unicameral form of government in order to ensure greater political stability. However, both have been accused of attempting to change the constitution to extend their stay in power. The Philippine experience with President Marcos’ attempts to perpetuate himself in power have reduced the general public’s tolerance to any changes to the Constitution, despite valid calls for constitutional reform.

Beyond rhetoric: the reality

Despite the poisonous rhetoric surrounding current debates on constitutional reform, there is merit to some of the arguments supporting constitutional change. The 1987 Constitution was designed with empowerment foremost in the minds of its framers. To its end, the Constitution supported the creation of stronger and more autonomous local government units. While this helped strengthen the capacity of local governments in shaping the direction of their own socio-economic development, it also created several problems which have now become apparent. For one, the devolution of rural and urban development planning has had disastrous effects for communities with poor planning capacities and insufficient political will. Typhoons Ketsana, Parma, and Lirio exposed the devastating consequences of shelving important infrastructure projects such as floodways and urban drainage systems, as well as the perils of creating weak and divided institutions for responding to natural disasters. In essence, localization and decentralization have contributed to the fragmentation of state responses to security and development challenges, and contribute to the ineffective implementation of policies.

However, one should not go too far to call for the re-establishment of an authoritarian and heavily statist form of government. The problem here is not whether an effective state is centralized or not, but the question of how authority and power are distributed and to who they are distributed to.

Certain functions of government need to be centralized to enable coordination and coherence, in order to achieve certain goals. Areas which require centralization include macroeconomic planning, national defense strategies, standards for infrastructure planning as well as the plans themselves, and standards for education and health. For these areas, parity and consistency matter more than policy independence and local oversight. The establishment of central institutions with sufficient planning and executive power can enable better planning, implementation, and monitoring of policies. Bigger, centralized bodies also have more resources and are thus better equipped to deal with large, complex problems such as economic security and disaster vulnerability.

Areas that should remain decentralized include oversight over the local implementation of infrastructure projects, the power of communities to utilize a generous portion of the taxes and revenue they earn, and the ability of local communities to voice their concerns over development to the national government. What these areas have in common is that they are all concerned with promoting the accountability of national governments to local communities, to ensure optimum outcomes for all actors from the individual in a local community to amalgamated business interests.

As for the question of what political system is best suited for the country, neither the Presidential nor the Parliamentary forms of government have the potential to contribute to better governance unless incentives and penalties for the behavior of public officials are better designed. Greater incentives for performance and the maintenance of law need to be provided, and punishments for illegal behavior and abuse of power need to be increased. This is why I refuse to espouse any specific form of government at this time, as I believe that simply changing the overlying structure of the state will do little to change underlying dysfunctions and inefficiencies.

A Post-mortem

Quo vadis, Arroyo?

However, the utility of constitutional reform depends on the intentions of the leader spearheading them. It is quite clear that President Arroyo and her supporters have not commented on the details of their proposed constitutional reforms. All that has been made clear is that the Presidential system doesn’t work, and that a Parliamentary system will. Exactly how that will happen has not been expressed, and only deepen suspicions that Arroyo wants to use a Parliamentary system as a piggyback to retaining power as an elected Prime Minister. Unless she is able to articulate clarify her intentions, this attempt to amend the Constitution, like so many efforts before it, is doomed to fail.

Will the leader who will succeed Arroyo be able to take up this challenge successfully? We shall see.

Leave a comment